The last time I saw Willie was not in the flesh but in a recent television documentary about the late, great Jim Baxter. In the documentary, we saw part of Willie’s eulogy to one of the finest footballers Scotland has ever produced and it feels entirely appropriate to me that this was the last glimpse I had of Willie. He was speaking from the heart about a man who was a genuine working class hero, who gave joy to millions. And when I think of Willie as a crime writer, I can never forget the way the Laidlaw trilogy gave a voice to the working class people of Scotland. Like Baxter, Willie was a working class hero whose work embodied grace, elegance and wit. But he did it in a way that remained intimately connected to where he came from.

I can still remember the shock of reading Laidlaw when it first appeared in 1977. I had never read anything quite like it. The dialogue resonated in my head because it captured the way people speak. The cadences and rhythms, the grammatical formations and the colloquialisms mimicked natural Scots speech and yet Willie gave it an elegance and eloquence that made it almost poetic. Jack Laidlaw’s world felt tangibly real. And somehow it was possible to believe in a Glasgow polis who kept a copy of Camus in his desk drawer.

It’s hard to remember what the landscape of British crime fiction was like in 1977. Mostly, it was pretty cosy. Unlikely murders in small towns and villages, cops who were either dead ringers for Dixon of Dock Green or part-time poets. Convoluted plots that ended with the least likely suspect having committed the most improbable crime. What Willie gave us was something completely different.

The impact of that first encounter reminded me of what Raymond Chandler said about Dashiell Hammett in his landmark essay, The Simple Art of Murder. He said, ‘Hammett gave murder back to the kind of people that commit it for reasons, not just to provide a corpse; and with the means at hand, not with hand-wrought duelling pistols, curare and tropical fish. He put those people down on paper as they are, and he made them talk and think in the language they customarily used for those purposes.’

Really, I couldn’t have put it better myself when it comes to describing what Willie did with his first thunderclap entry into the crime genre.

It’s all the more remarkable because up to that point, Scotland had no tradition of crime fiction. There are a few figures in the landscape – The Confessions of a Justified Sinner, Jekyll and Hyde, Conan Doyle, Josephine Tey. But that doesn’t add up to an obvious tradition to adopt and carry forward.

But Willie saw that the crime novel offered an interesting set of possibilities. By its nature, it opens up a broad potential range of characters. Victims, witnesses, cops, killers, all with their own social circumstances and their own individual hinterlands. Laidlaw gave Willie the chance to cast his net wide over the city he inhabited and he grabbed that opportunity with both hands. In 1977, I was a young journalist in Glasgow, and Laidlaw was a kind of totem for me, a text that illuminated the city I saw through the editorial car windows every night. For all its violence and poverty, Willie made me see it also possessed a kind of dirty romance.

What Laidlaw also did was to show that the crime novel could be more than a pulp entertainment. That it could shine a light on the society it came from and show how our crimes have their roots in how we live and the choices we make. That it could be well written and tell us uncomfortable truths about ourselves. That it was a natural home for great story-tellers. In short, he made it look like something writers should aspire to, not be ashamed of.

Now, the genre of Tartan Noir is known the world over. We’re invited to speak about it from Australia to Mexico, from Iceland to South Africa. It is no exaggeration to say that without Willie, it wouldn’t exist. Dozens of Scottish writers have found a voice and an audience well beyond these borders because Willie showed us what was possible. We’ve explored every aspect of our complicated national psyche thanks to the lead he took. We’ve subjected readers all over the world to the black art of Scottish humour and made them wince at our ability to laugh in the teeth of disaster.

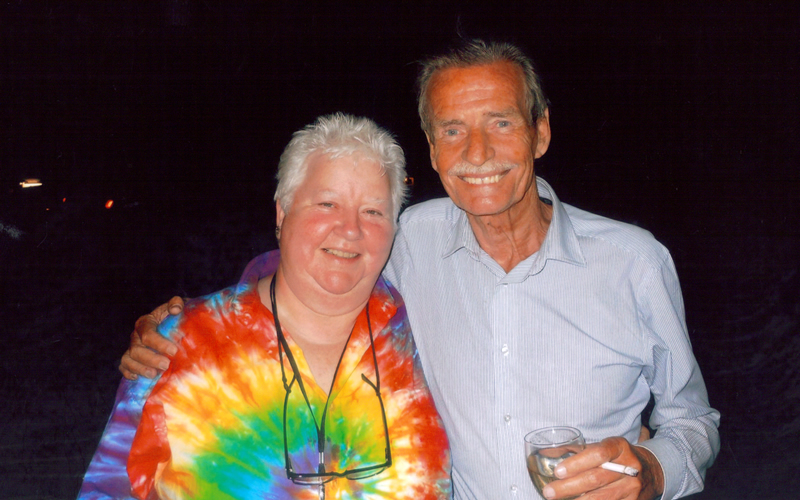

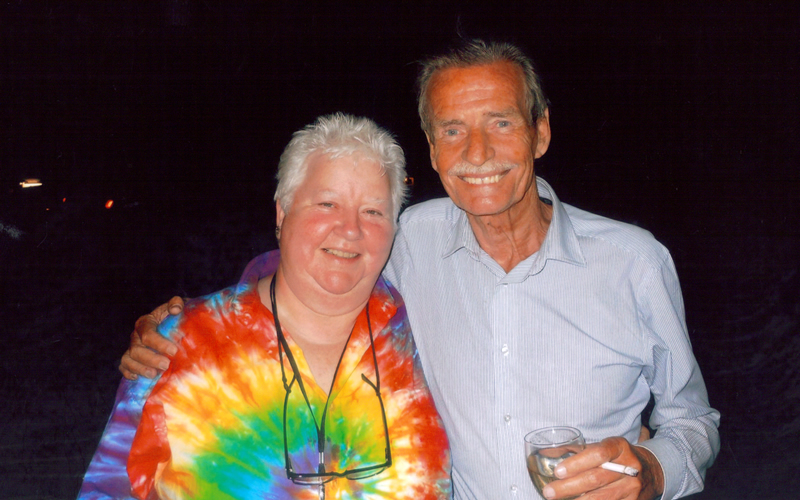

That would be enough of a legacy for anybody, really. But Willie gilded the lily of his work with his personality. He was wonderful company. Generous, clever, full of insights and questions, charming and funny. It’s a terrible cliché that he would have taken the piss out of me for, but he did light up a room. But then, I don’t have to tell you that. You’re here today because you know that already.

I doubt I’d be standing here today if it wasn’t for Willie McIlvanney’s contribution to crime fiction. He cracked open a door that revealed possibilities young Scottish writers hadn’t really considered before. Ian Rankin and I shouldered that door open a wee bit further, and then we were joined by a tidal wave of others who saw that this was a way to tell great stories at the same time as exploring who we are in the world.

I feel profoundly grateful for Willlie’s contribution to crime fiction. It changed the course of my life, and I’m not the only one by a long chalk. I’m glad that in recent years, thanks to festivals like Bloody Scotland and Harrogate, he saw for himself the value we all placed on him and his work. I’ll leave the last words to the man himself, from Strange Loyalties, the final instalment of the Laidlaw trilogy:

“He had lived with such intensity. The thought was my funeral for him. Who needed possessions and career and official achievements? Life was only in the living of it. How you act and what you are and what you do and how you be were the only substance. They didn’t last either. But while you were here, they made what light there was – the wick that threads the candle-grease of time. His light was out but here I felt I could almost smell the smoke still drifting from its snuffing.”

Val McDermid

From the William McIlvanney Memorial Service, 2nd April 2016

|